By Mónika Simon & Rupert Kiddle

What is Telegram and why should we study it?

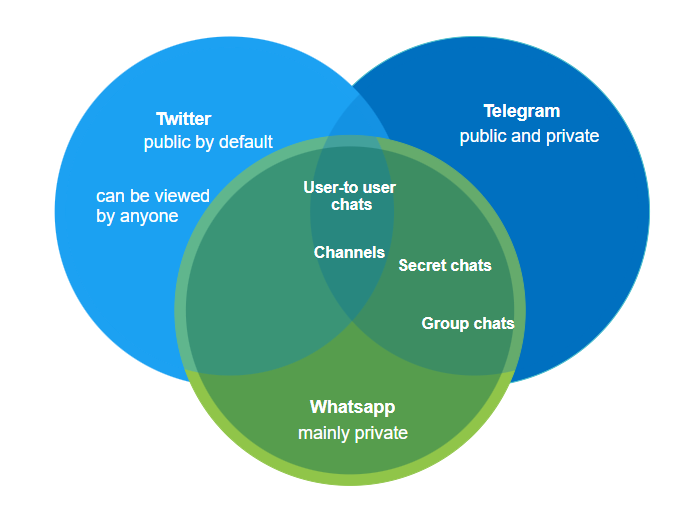

Telegram is the largest, cloud-based, hybrid instant messaging (IM) application that can be accessed via smartphones, tablets, or desktop. It has several privacy-enhancing features that are arguably attractive to those who seek a platform that offers opportunities for publicity and mobilization whilst also safeguarding their anonymity in order to avert possible legal repercussions [1, 2].

Aside from these privacy-enhancing features, at its core Telegram offers two main means to converse: Channels (private or public) primarily enable one-sided communication toward an unlimited number of followers, whereas group chats (private or public) can host mass discussions among hundreds of thousands of members. No other IM app provides a space for discussion or broadcast between this many people.

Telegram’s easy-to-access public space has recently become a popular new discussion arena among those who feel censored by the stricter moderation policies of mainstream social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook Telegram is the largest, cloud-based, hybrid instant messaging (IM) application that can be accessed via smartphones, tablets, or desktop. It has several privacy-enhancing features that are arguably attractive to those who seek a platform that offers opportunities for publicity and mobilization whilst also safeguarding their anonymity in order to avert possible legal repercussions [1]. In our view, this makes Telegram a dark platform Telegram is the largest, cloud-based, hybrid instant messaging (IM) application that can be accessed via smartphones, tablets, or desktop. It has several privacy-enhancing features that are arguably attractive to those who seek a platform that offers opportunities for publicity and mobilization whilst also safeguarding their anonymity in order to avert possible legal repercussions [3]: one which welcomes the ‘deplatformed’ with open arms though policies of content liberation. The darkness of a platform, however, can be viewed in both positive and negative lights. Telegram has been the subject of media and scholarly attention as much for its ability to liberate marginalized communities as it has been for its potential to radicalize users who are exposed to extremist content.

Yet, we know little about the role of the increasingly popular but more secluded online spaces such as Telegram in fostering the formation of like-minded communities despite an increasing shift toward using IM apps (e.g., WhatsApp, WeChat, and Telegram), rather than large SNSs (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) for news consumption and discussion [4].

Given Telegram’s growing popularity amongst (deplatformed) digital exiles, and high potential for news dissemination, information consumption, mobilization, and radicalization, we set out to study information flows – with an emphasis on politically and socially relevant topics – within the Telegramsphere using the Netherlands as a case study.

Similar explorations of several Telegram chats were conducted by the Utrecht Data School, which were previously covered by Dutch media.

Insights about the Dutch Telegramsphere

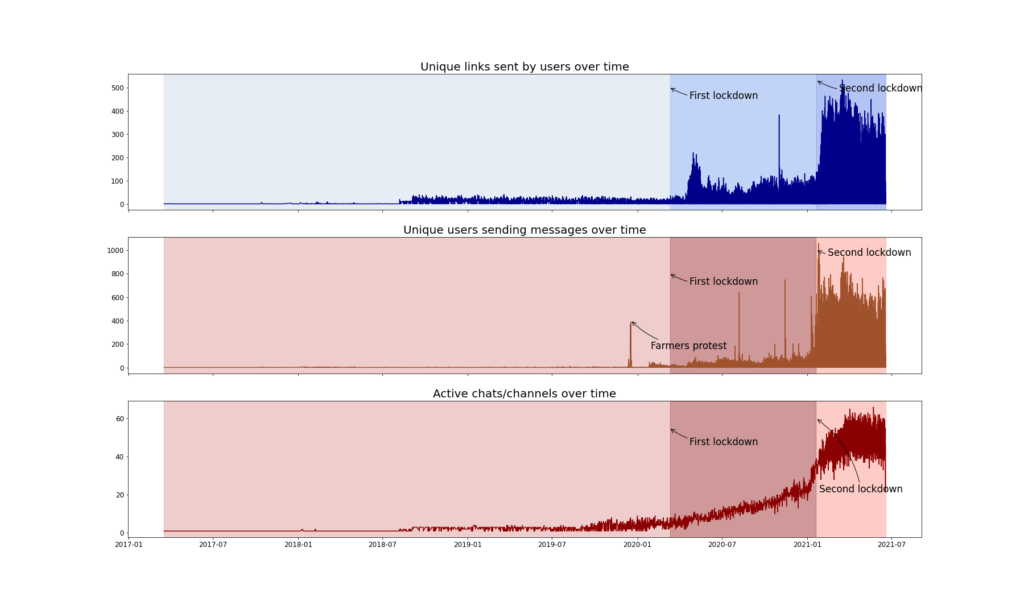

We analyzed the full messaging history (18/03/2017 — 18/06/2021) of 174 Dutch language chats (n = 80) and channels (n = 94) via a list of public Telegram chat and channel URLs that we fed into the Telethon Python library, which interacts with Telegram’s API. The channels and chats were identified via a list of access words (using the Telegram desktop app) that were related to current affairs (e.g., news, politics, names of political parties and their leaders). Given that at the time we conducted the study the Coronavirus pandemic represented a prominent issue of both the media agenda and the public agenda alike, we also included search terms that were directly related to COVID-19 and activism against COVID-19 safety measures (e.g., freedom, awakening, protest, etc.).

We analyzed a total of 2,033,661 text messages. These were sent by 55,331 unique users. Within these messages, users shared a total of 217,428 unique URLs; these belonged to 11,463 unique domains (i.e. websites). A large proportion of these links (28%) point to well-known social media platforms. These include Youtube, comprising a remarkable 18% of shared links overall (35,232 videos); Twitter with 6% (13,580 tweets), Telegram (3%) and Facebook (1%).

We found a total of 33,780 emojis in users’ text messages. The most frequently used emoji was

’👍’ (thumbs up – 7,070 times) followed by ‘😂’ (face with tears of joy – 3,344 times), and ‘🖤’ (black heart emoji 2,519 times).

What could these findings mean?

We found a large diversity of unique website references within text messages, which suggests that Dutch Telegram users consume information that comes from outside of Telegram. The highest proportion of the identified links pointed to content from well-known SNSs such as YouTube or Twitter, which may indicate that Dutch Telegram chats and channels are well connected to other social media platforms. In fact, given the low proportion of Telegram links shared within messages, we speculate that the Dutch Telegramsphere has stronger cross-platform linkages with mainstream SNSs than interplatform ones between Telegram chats and channels. Following this train of thought, we suspect that those who use Telegram are not stuck in Telegram bubbles (at least not with regard to the sources they referred to within text messages). Future research must also consider the way users refer to these external sources, given that those who refer to content from mainstream media may simply do so to express their disagreement with it. For example, one could share an external source to debunk its validity.

Emojis appeared to play an important role in how Dutch Telegram users expressed themselves. Looking at the most common emojis used within text messages it is unsurprising that the most popular ones were ’👍’ and ‘😂’ given that these emojis are also prevalent on other messaging platforms. The frequent use of the ‘🖤’ represents a more puzzling finding. According to Emojipedia, it symbolizes sorrow, grief, dark humor, or morbidity. We speculate that the prevalence of the black heart emoji within the Dutch Telegramsphere could symbolize a reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic and the strict lockdown measures introduced by the government to combat the crisis. However more thorough analysis is needed to uncover the exact meaning of this symbol within the analyzed chats and channels.

The second part of this report will delve into more specific findings using the extracted URLs.

References

@article{rogers_deplatforming_2020,

title = {Deplatforming: {Following} extreme {Internet} celebrities to {Telegram} and alternative social media},

volume = {35},

issn = {0267-3231},

shorttitle = {Deplatforming},

url = {https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120922066},

doi = {10.1177/0267323120922066},

abstract = {Extreme, anti-establishment actors are being characterized increasingly as ‘dangerous individuals’ by the social media platforms that once aided in making them into ‘Internet celebrities’. These individuals (and sometimes groups) are being ‘deplatformed’ by the leading social media companies such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube for such offences as ‘organised hate’. Deplatforming has prompted debate about ‘liberal big tech’ silencing free speech and taking on the role of editors, but also about the questions of whether it is effective and for whom. The research reported here follows certain of these Internet celebrities to Telegram as well as to a larger alternative social media ecology. It enquires empirically into some of the arguments made concerning whether deplatforming ‘works’ and how the deplatformed use Telegram. It discusses the effects of deplatforming for extreme Internet celebrities, alternative and mainstream social media platforms and the Internet at large. It also touches upon how social media companies’ deplatforming is affecting critical social media research, both into the substance of extreme speech as well as its audiences on mainstream as well as alternative platforms.},

language = {English},

number = {3},

urldate = {2021-03-26},

journal = {European Journal of Communication},

author = {Rogers, Richard},

month = jun,

year = {2020},

keywords = {Deplatforming, Digital Methods, Extreme Speech, Social Media, Telegram},

pages = {213--229},

annote = {Publisher: SAGE Publications Ltd},

}@article{urman_what_2020,

title = {What they do in the shadows: examining the far-right networks on {Telegram}},

shorttitle = {What they do in the shadows},

journal = {Information, communication \& society},

author = {Urman, Aleksandra and Katz, Stefan},

year = {2020},

pages = {1--20},

annote = {Publisher: Taylor \& Francis},

}@article{zeng_conceptualizing_2021,

title = {Conceptualizing “{Dark} {Platforms}”. {Covid}-19-{Related} {Conspiracy} {Theories} on 8kun and {Gab}},

volume = {0},

issn = {2167-0811},

url = {https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1938165},

doi = {10.1080/21670811.2021.1938165},

abstract = {This study investigates how COVID-19-related content, especially conspiracy theories, is communicated on “dark platforms” — digital platforms that are less regulated and moderated, hence can be used for hosting content and content creators that may not be tolerated by their more mainstream counterparts. The objective of this study is two-fold: First, it introduces the concept of dark platforms, which differ from their mainstream counterparts in terms of content governance, user-base and technological infrastructure. Second, using 8kun and Gab as examples, this study investigates how the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has been communicated on dark platforms, with a focus on conspiracy theories. Over 60,000 COVID-19-related posts were studied to identify the most prominent conspiracy theories, their themes, and the actors who promoted them, as well as the broader information ecosystem through network analysis. While pressure on social media to deplatform conspiracy theorists continues to grow, we argue that more research needs to be done to critically investigate the impacts of further marginalizing such groups. To this end, the concept of dark platform as can serve as a heuristic device for researching a wider range of fringe platforms.},

number = {0},

urldate = {2021-06-18},

journal = {Digital Journalism},

author = {Zeng, Jing and Schäfer, Mike S.},

month = jun,

year = {2021},

keywords = {8chan, 8kun, conspiracy theory, COVID-19, dark participation, Gab},

pages = {1--23},

annote = {Publisher: Routledge \_eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1938165},

}@techreport{newman_reuters_2019,

title = {Reuters {Institute} {Digital} {News} {Report} 2019},

language = {English},

author = {Newman, Nic},

year = {2019},

pages = {156},

}